The exact birth of the Renaissance is widely disputed. The Renaissance itself was a glittering period in Europe that bridged the fire and brimstone of the Middle Ages, and the more recent era of Modern History. It was a time of much mulling and scratching of bellies that drew heavily on the principles of humanism; a movement or method of learning steeped in the thinking and history of classical antiquity. It was essentially a cultural movement, expressed through art, architecture, politics, science and literature. It established the refreshing use of perspective in art and saw the flowering of Latin. It sparked educational reform, diplomacy and an increased reliance of observation in science. It was a time that scorched the status quo and revelled in the brilliance of the human mind. Polymaths, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, inspired a liberation of thought and individual expression. A polymath was, or indeed still is, a person whose expertise spans a diverse number of different subjects. In Renaissance times these were typically men, whose voracious curiosity and fertile imagination inspired the age and spawned the term Renaissance man – an all-singing all-dancing fellow of debutantes’ dreams.

The most likely birthplace of the Renaissance though was Florence, the Tuscan town in the belly of Italy famed for its museums and spectacular artistic heritage. Forbes magazine, the American Business Journal, voted Florence one of the most beautiful cities in the world, but then Forbes magazine is based in Jersey City, New Jersey; part of the New York metropolitan area so perhaps that is not a huge surprise. The origins of the Renaissance occurred in the late 13th century, when artists and writers with exotic names such as Ghiberti and Brunelleschi and Giotto di Bondone, dared to think out loud. Some writers suggest the Renaissance was born when the rival brilliance of Ghiberti and Brunelleschi went man-a-mano for the contract to build the bronze doors of the Baptistery of the city’s Cathedral. Others disagree. Basically no one knows. What else, no one seems be too sure on, is why Italy specifically should have been the crucible of high-brow reflection on the whole being bit of being human. Some point to the fragmented political structure of late Middle Ages Italy, which produced a social climate conducive to letting go of established doctrine. Others suggest the custom of wealthy families bank rolling the arts provided the means for artists to spend their days and nights getting hooped on cheap Chianti and throwing paint on bare canvas. One theory even proposes the Renaissance came about as a result of the Bubonic plague which nearly wiped out Europe in 1348. The thinking being that the plague was particularly rife in Italy and with the locals staring down death on a daily basis, it gave cause to take a step back and think about life in the context of basic survival as opposed to the ethereal realms of spirituality and the afterlife. The plague though wrought death across the whole of Europe, and so perhaps failed to explain why the sober reflection of one’s ill-fated lot was confined to Italy. The obvious conclusion is that perhaps there wasn’t one specific catalyst, and it was a combination of many things. Either way Italy, and Florence, were at the epicentre of a redefinition of what life was all about. It must have been, peasant life aside, an exhilarating time to live.

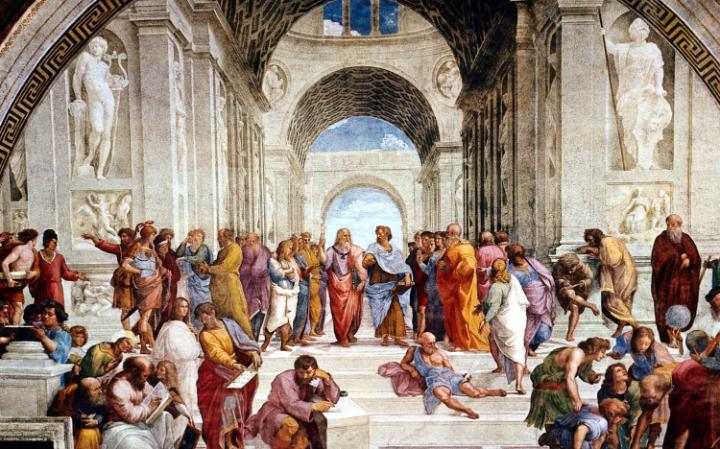

Whilst the Renaissance period influenced many walks of life, it was in art that it really walloped it out the park. It was basically a cultural re-birth, sponsored by those whose wealth had crushed any sort of creativity out their own earthly being. Giotto di Bondone is, today, widely regarded as the pioneer amongst the great painters, a man who first treated the canvas as a window into space. Later artists embraced the use of perspective, in addition to pushing the boundaries in light, shadow and famously, in the case of the straight-A Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Architecture was given a fresh pair of socks by Fillipo Brunelleschi, he of the Florence baptistery gate-off, a man who is talked of at middle-class dinner parties as the most inventive and gifted designer of all time. For those too tuned in to demolishing the Rioja at such occasions, Brunelleschi’s most admired work was the building of the exquisite dome of Florence cathedral. Box ticked. In Science, ancient texts were given a new lease of life and some clever bean worked out how to print stuff on paper, a development which revolutionised learning, opening up the vaults of history to those who could read, and fuelling the broader proliferation of ideas. Music too benefitted from the new age of the printing press and religion was particularly affected by the way the common herd viewed their relationship with God. In England, names from the domestic effort to high-brow revolution which might prompt throaty growls of acknowledgement included the “Bard of Avon”, William Shakespeare, and also Christopher Marlow, Sir Thomas Moore and Francis – the daddy of empiricism – Bacon. Legends, each to a man.

Perceptions of the period are, though, perhaps skewed by the brilliance of the likes of da Vinci and Shakespeare and whilst the cultural change could be likened to a veil being removed from man’s eyes, there were other aspects of the medieval period such as wars, poverty and the horrifying persecution of witches that suggested social progress was a bit rocky. The Marxists, those disruptive, itchy revolutionaries who want to bury the bourgeoisie in their own compost, took a more palid view of affairs and saw the Renaissance as a time when feudalism was replaced by capitalism to the benefit of those who had the time and inclination to care about the introduction of perspective in paintings. Johan Huizinga meanwhile, the acclaimed Dutch historian, reckoned the Renaissance was actually a period of cultural decline whilst others argued that the progress in disciplines such as science were less original than is widely supposed. They are though the minority. For everyone else, the museums of today would be a lot quicker to go round were it not for the classical pieces of the age. History, like beauty and children, is often best appreciated in the eyes of the beholder.