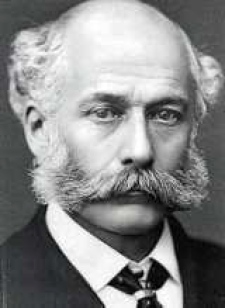

It was the great stink that started it. July 1858 and London was hot. Hot like Spain. Nice in the context of deck chairs and Soleros in Green Park, not so nice in the context of the raw effluence on the street and general industrial waste that floated up and down the Thames; all of which caused, well, a great stink. Before Thames Water got to routinely dig up all the roads and prod the violent inner psychopath in all inner-city commuters, there were no tunnels, no pipes or sewers to take away the squalid waste of daily life. It was against this backdrop of simmering social unrest and cholera that the authorities received a proposal from Joseph Bazalgette to stick in some underground sewers to take the sewage out from the metropolitan area and dump it somewhere closer to Essex. The system remains in place to this day and Bazalgette probably saved more lives than any other public official who has ever stood in office since. Bazalgette is a hero.

Joseph William Bazalgette was born in Enfield, a town that was once about a day’s travel north of London. Then the railways got built. Then the Piccadilly Line brought Enfield into play for lunch, should anyone have been so inclined. There is little recorded of his schooling for the idle reader, but given he went down in history as one of the great Victorian engineers, you can assume some schooling happened and he did rather well. After leaving education, he went on to become heavily involved in the expansion of the railways and, having spent some time in Ireland where he learnt about drainage, reclamation and drinking before lunch, he returned to London and set up a consultancy. It was a crazy time to be working on the railways. All work and no play. Indeed, so much work, that Bazalgette soon had a breakdown.

London at this time was nothing more than an open sewer. It’s difficult to imagine walking down Oxford Street now, but back in the day, it was no place for a pair of fawn loafers. There were no fish in the Thames either. So in some respects just like today then. Now after a stretch of light R&R, Balzagette bounced back and joined the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, a commission that was established to sort out the mess after thousands of Londoners kept getting picked off by cholera. In 1852 Bazalgette took over as chief engineer after his predecessor quit, hounded out by his own inner demons and by the time of the Great Stink, Bazalgette was heading up the Metropolitan Board of Works. London was ready for his big idea and Parliament – aristocratic and heeled in fine leather brogues – was all over it and agreed to underwrite the whole whopping proposal.

The proposal was essentially to stick in miles and miles of brick sewers linked with other sewers that delivered the raw sewage from the streets. But you ask, “how big the sewer?” Good question. Bazalgette himself asked the very same question. Demonstrating the foresight of a man destined for a knighthood, he took the densest part of London and then worked out – it is not recorded how – how much waste each individual would produce every day, to come up with the diameter of the pipes involved. He then whispered to his underlings to double it. London would later, through tower blocks and hot-bedding Australian barmen, more than double in density, a development that would have overwhelmed the sewer system had Bazalgette not had the foresight to go big. Remarkably, he insisted on signing off it all himself. Not the project, but each and every nut and bolt. The new sewer system virtually eliminated cholera, and significantly reduced the incidence of typhus and typhoid. That London’s sewage system remains in place to this day, is even more remarkable. As I said, a hero.

Sir Joseph Bazalgette died in Wimbledon in 1891.